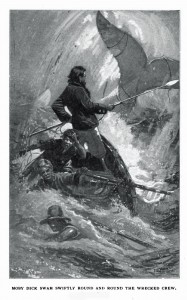

The oddest intellectual disjuncture of parenting so far has come during my quiet hours of feeding the baby her bottle. I’ve been listening to books on tape audiobooks* while she drinks, because bottle feeding requires two hands, considerable attention, and a healthy dose of patience. I’ve been mostly consuming nineteenth century novels, because it can’t hurt to bone up on some of the century’s doorstop classics, which are mostly too long to work into my regular rotation of professional reading. I tend to gravitate to books that I know, but not particularly well, and which don’t directly bear on my research but which are important in the overall sweep of cultural and intellectual history of the nineteenth-century U.S. It also doesn’t hurt that you can download public-domain books on tape audiobook (generally pre-1923) from Librivox for free, and I’m too cheap to pay for Audible. Most recently, I’ve been wading through Moby-Dick, at the rate of two or three chapters per 7 ounces of milk. (Melville’s chapters are short, and the baby likes to take her sweet time.) I am quickly coming to the conclusion that Moby-Dick was a deeply weird choice for the particular context of baby feeding. Read more

Ahab Among the Innocents

Trump the Small-‘r’ Republican?

As Frank Rich pointed out in his recent meditation on the political phenomenon of Trump, political observers and pundits have struggled to identify historical precedents. The most popular, according to Rich, have ranged “from the third-party run of the cranky billionaire Ross Perot back to Huey Long and Father Charles Coughlin, the radio-savvy populist demagogues of the Great Depression.” He also fingers Joseph McCarthy, Hugo Chávez, George Wallace, and his favorite, the fictional, comedic “unhinged charlatans” of Mark Twain. For Rich, Trump is the real-life embodiment of the fictional political con-men of American cinema, characters who though their sheer outrageousness call into question the legitimacy and sanity of the political system as a whole. Rich foresees some potentially salubrious effects of Trump’s brazen act of real-life political satire, because his performance will lay bare precisely how naked the emperor really is, thus necessitating reform. I think that’s exuberantly optimistic, to the point of naiveté, although he gets points from me for trying to find a silver lining the dark cloud of Trumpism. But I’d like to suggest another older and more jarring precedent for Trump: the “Founding Fathers” themselves.

Apparently the Liberal Arts Aren’t Irrelevant

I have been noticing an increasing drumbeat in recent months of arguments that despite all “evidence” to the contrary, the liberal arts are neither dead nor irrelevant. These arguments tend to emerge out of one of two motivations, either passionate defense of deeply held personal values by the liberally-educated, or contrarian quarrelsomeness by those looking to stick a thumb in the eye of the current political consensus in favor of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math). File this current example from Forbes in the second category, since it is penned by a business journalist who is interested in “the surprising value of a liberal arts degree in our tech-crazy world.” The article’s broader argument is the even tech companies need employees with social and cultural training to sell their products to actual human beings. I’m not sure I’m overjoyed that the measure of the liberal arts’ value is their ability to train better salespeople for the doublespeaking masters of the universe in Silicon Valley, but in the current climate of political skepticism about the value of humane education, I’ll take whatever allies I can get. Oh, and speaking of historians and high tech, this video still makes me want to die laughing.

Removing the Confederate Flag is Not Nothing

You get credit, Richmond, when you take down those statues on Monument Ave. Except Arthur Ashe. He can stay.

After I heard about the horrific church shooting in Charleston on June 17, I have to say that the last thing I would have predicted is a wholesale, bipartisan war on the Confederate flag. I expected the brief, heart-wrenching, and futile discussion of gun control; I expected the calls for a “national conversation about race” (whatever that means); and I expected the general sense of self-congratulation that Americans now at least express sadness in moment of racial terrorism. But I didn’t expect such a wholesale revisiting of the politics of the stars and bars. And I definitely didn’t expect that revisiting to be happening among members of the Southern right. Politics are an unpredictable beast. Read more

Have I mentioned I grew up in Brothertown?

Due to a very happy arrival in our family, Brian and I were legally required to cool our heels at my parents’ house in southern Oneida County in central New York, where I grew up. Our enforced (albeit highly enjoyable) 3-day visit reminded me that the little valley where I spent my childhood was the site of an interesting episode in the history of the early republic. Beginning in the 1780s, the upper valley of Oriskany Creek was the location of the first Brothertown.

A Declension Narrative of Paperwork

Of all the contributions that historians can make to contemporary public discourse, I think that reflective skepticism about declension narratives is one of the most important. Historians define “declension narratives” as any story of change over time that trace a secular decline, decrease, or deterioration in a historical phenomenon. In other words, a declension narrative is any story we tell about something getting progressively worse (not just different) over time, in a non-cyclical way. Once you become aware of the existence of declension narrative, you’ll begin to notice that they’re everywhere in our culture. Two places I notice them all the time are in the discourse of generational change (check out ANY article about the so-called “millennials”) and in any discussion of the liberal arts in modern society.

Capitalism is an Empty Signifier

Back in January, I posted about a project that my Cultural History of Capitalism seminar was undertaking this semester. Students in the class had to go out and interview three people about how they understood both the meaning of capitalism as well the history of capitalism, and then they had to write a reflection post on their conclusions about popular meanings and histories of capitalism, and how those popular understandings match up with the scholarly literature on the subject. The project is done, and it has turned out to be an interesting and revealing, if not particularly surprising, exercise in muddiness. The class’s interviewees often had strong feelings about capitalism, which showed a good deal of variation from strongly positive to strongly negative to deeply ambivalent. But when we pushed harder, the interviewees generally had a difficult time saying exactly what capitalism was, and an even harder time tracing its history. People knew it had something to do with “markets,” and often “freedom,” and that it came from England, and that Adam Smith was an important guy. Beyond that, most of the interviewees demurred.

In Case We Doubted that Scholarship is Social

I have just returned from the Annual Meeting of the American Association of Geographers in Chicago. I’m obviously not a geographer, but I got an opportunity to talk about my work on the print culture of geographical knowledge in the nineteenth century at the conference, and I got excited about the possibility of talking about that work to a group of non-historians who would nevertheless be interested in it. It ended up being a great experience, but also a really odd one, because attending the main annual conference of a discipline that is not your own is an odd kind of outsiderism.

I did not feel particularly out of place intellectually. I know something about the scholarly practice of geography; I know something about how the discipline developed in the nineteenth century, and I know something of its parameters from interacting socially and professionally with practicing geographers. Also, geography really sprawls as a discipline, and seems to find a place for pretty much any topic or any methodology. The sense of outsiderism was social, not in the sense that people were rude or unfriendly, but in the sense that I was walking into an ongoing conversation in the middle and had to struggle to figure out what people were talking about and why they cared.

Yik Yak is the Id of the University

It has been a tumultuous 24 hours at UMW, since the Virginia State Police rolled in last night and arrested some protesters who had been occupying the administration building for the past three weeks in an attempt to get the university to divest its portfolio from fossil fuels. It has been interesting, to say the least, to watch the controversy play out in different media.

Millennials Should Learn Trades, Say College Educated Writers

This NPR piece, and other like it based on the arguments of economist Anthony Carnevale of Georgetown University, have been making the rounds on my social media over the past few weeks. The NPR journalist, Chris Arnold, builds on Carnevale’s work to argue that millennials should pursue training in skilled trades like “pipe-fitters, nuclear power plant operators, carpenters, welders, utility workers,” because baby boomers are retiring and not enough workers are being trained to replace them.* College isn’t for everyone, the argument goes, and well-trained skilled tradesmen make good money, especially compared to workers with only a four-year college degree. As a society, we need to make training in the trades easier to get and remove social stigma from careers built on working with your hands. Read more