Fredericksburg can be a weird place to live. If you stay downtown, life flows smoothly and easily along, with relatively few delays and inconveniences. But if you leave “the bubble” (as Brian calls it) then things get ugly really fast. I don’t care what they say, Fredericksburg is part of Northern Virginia if you define Northern Virginia as a region of unrestrained, sprawling growth that produces horrific traffic. Primary and secondary roads around town, and especially I-95, get incredibly clogged during rush hour, on summer weekends and holidays, and any time there is the slightest hiccup due to weather, construction, or accidents.

So I was relieved to see Earl Swift’s great piece on The Atlantic Cities blog entitled “Putting a Price on DC’s Worst Commute.” Not to spoil it, but DC’s worst commute is on I-95 between Fredericksburg and the District. Partly, I really liked this piece because it confirmed that I’m not crazy. I think the Fredericksburg’s traffic is horrible, and calling it the worst commute in DC, which is widely regarded as being one of the traffickiest metro areas in the US, offers authoritative support to my personal experience. But mostly, I like Swifts’s questioning of whether or not the ongoing expansion and extension of the HOV/HOT lanes will solve the problem.

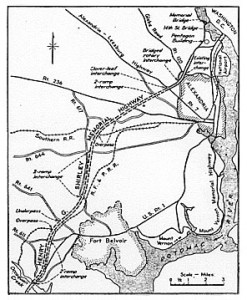

A bit of background for non-locals and non-historians: there is a pair of reversible lanes built in the median of I-95 that extend from the Pentagon about halfway to Fredericksburg. The expressway was begun in 1941 as the Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway, built to speed traffic into the city from the growing suburbs of Northern Virginia. When it opened in in 1949, it featured a single reversible bus lane in the median, which at the time was a cutting-edge way to move enormous number of 9-to-5 commuters from the bedroom communities of the Old Dominion to the endless office cubicles of the District. Over the years, the reversible lanes have been opened to carpools, widened, and extended further and further into Virginia, to their current terminus halfway to Fredericksburg.

These lanes are currently undergoing massive privately-financed construction. They’re being widened to three lanes in closer to DC, and extended down into Stafford County (headed, if old plans are still to be believed, all the way to Fredericksburg). As a condition of the private financing, the HOV lanes are being converted to HOT, an awkward acronym indicating that the lanes are now open to single occupancy vehicle if the driver pays a toll. They’ll still be free for carpoolers, but now non-carpoolers can pony up for a quick ride. The toll will vary depending on how full the lanes are; as they fill, the toll will go up, and as they empty, it will go down. This idea, called “dynamic tolling,” is supposed to keep the lanes at their ideal capacity, full enough to be useful but still moving quickly. And it’s a way to get infrastructure without spending tax dollars.

Swift’s piece is about this idea of dynamic tolling, and about whether or not it works as well in practice as it does in theory. The evidence seems to be mixed, and Swift’s piece ends on a note of ambivalence. Myself, I’m agnostic on the issue, and since I’m not an expert on transportation infrastructure, I’m not really qualified to judge. Although I will anyway; as a historian of capitalism, I am hyperaware of ways in which market thinking and market logic get extended metaphorically and materially into new realms of life. Watching the ways in which market thinking has been used and especially abused since the nineteenth century, I am highly skeptical of both the practicality and the morality of any scheme that so crassly applies the magical sauce of supply and demand. In California, similar dynamic tolling schemes have been terms “Lexus Lanes,” a snarkily alliterative term that captures some of my skepticism.

But apart from my instinctual suspicion of magical market thinking, my insight as a historian of transportation suggests that they won’t do much to solve Fredericksburg’s traffic problems. The idea of the reversible rush hour express lane was conceived in a different era of urban planning. The postwar period was one of rapid suburban outmigration balanced by the continued vitality of downtown employment centers. Middle-class people increasingly lived in suburbs and worked in cities, which meant that the major transportation problem faced by a growing metropolitan area was how to get huge numbers of people into the city in the morning and out of the city in the evening. The reversible bus lane, and later the reversible carpool lane, was an elegant solution to that problem. (Well, not as elegant as trains, but the postwar period was alone one of major automobile fetishization.)

But the dynamic of urban/suburban land use has gotten a lot more complex since the 1940s. The movement of office jobs out of central cities began in the 1960s, and accelerated in the 1970s and 1980s, as employers followed their employees out of the city. And especially in the last twenty years, the children of the suburbs have increasingly been migrating back into the city in pursuit of the urban lives their parents fled. The sum total of these changes is that commuting patterns are much more complex now than they were when the reversible lanes were conceived. People live in the city and work in the suburbs, or live in one suburb and work in another. Half my department at Mary Washington lives either in the city or at least closer in than Fredericksburg. None of their commutes are served by the reversible lanes, and none of their commutes will be made better by their expansion.

And more-complex commuting patterns aren’t the whole problem. As ,more people move to the city or live in places where they can commute via public transit, car trips will increasingly be reserved for pleasure travel, in the evening and especially on the weekend. That’s already the way my family lives; my partner and I both walk to work, and use the car almost exclusively during non-work hours. The reversible lanes won’t do anything for drivers like us, either. Sure, they’ll ease traffic in one direction on the weekend, but the thing about weekend recreational travel is that it’s less likely to be directional, which means reversible lanes only address half the problem. So between changing commuting patterns and increasingly recreational car use, reversible lanes don’t seem to be a solution to today’s problems. And these trends seem to be accelerating, too.

So ultimately, I share Swift’s ambivalence, if for different reasons. Expanding and extending the reversible lanes may have addressed Fredericksburg’s traffic problems a generation ago, but today, they’ll only address one small part of them.

Leave a Reply